Yet another crisis (extra large) right on our doorsteps

The current decline of the world economy is no secret to anyone. The economic conditions are clearly moving in that direction, to the point that a new crash is feared to occur. Even if it does not go that far, the future is anything but rosy. Red lights are blinking all over.

In 2017, the 2008 crisis finally seemed to be behind us; global business was getting back on track and the outlook seemed to have improved, even within the European Union, which had been hit particularly hard. By the end of 2018, the Federal Reserve, the US central bank, had raised its interest rates from a historical all-time low of 0.25% to 2.5%, which was a clear sign of recovery, while at the same time the European Central Bank (ECB) was putting an end to its purchase of government bonds1. The darkest days seemed to be behind us. Until recently, that is, when the ECB, fearing a new recession, decided to restart this programme. The markets are entering a new zone of turbulence.

Capital strike

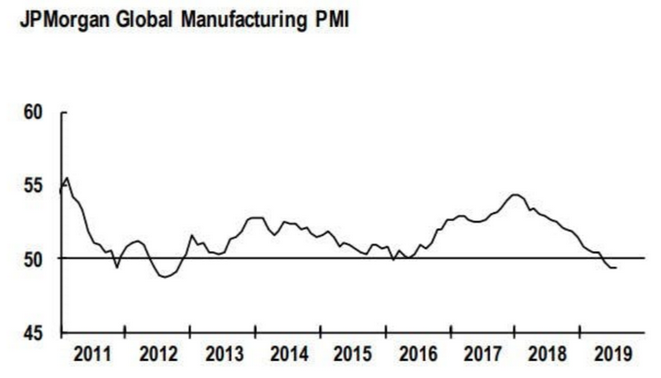

The clearest sign of the emergence of a crisis is the simultaneous and generalized slowdown in growth in practically all the major countries of the world. This sluggishness is mostly noticeable amongst the main economic actors at global level, i.e. the United States, China, Japan and the European Union. The countries in the eurozone have experienced lagging growth for the past seven months. In spite of the fact that it is a leading exporter, Germany is worst affected and is dragging its supplier countries down with it. Such a situation results from a decline in industrial production as well as a drop in investments and production of intermediary goods. For now, only services and consumer goods are protected from this generalized recession. This has been shown by the variations in the PMI that measures the evolution of industrial production and orders, thus reflecting the situation at global level most reliably. It is now at its weakest level since 2012.2

Ever since the 2008 crash, investments are now at an all-time low. The problem does not, however, result from a lack of capital. What is lacking are projects with what is deemed to be a sufficient profit margin: capital prefers more cost-effective solutions such as speculation and financial engineering. The IMF recently published a report showing that not less than 40% of the 15 trillion dollars’ worth of foreign investments are actually fictitious, non-productive investments in multinationals, whose only aim is tax evasion1. Half of such investments end up at our neighbours’, Luxembourg and the Netherlands, the most popular tax havens at present.

And that does not take into account the presently volatile international climate, particularly in the context of the ongoing and rapidly escalating trade war between the USA and China, which is only increasing concerns. As can be seen, the global economic outlook has not been as dark since 2009.

There is no mistaking the signs

The reactions of investment funds, pension funds, banks and insurance companies do not deceive, no more than the skittishness of stock markets when a slowdown in returns is approaching. The big investors withdraw one after the other, like rats deserting a sinking ship, they prefer focussing on the security of state bonds. Two sobering phenomena are usually harbingers of a crisis, and they can be observed right now. The first one is the inversion of the interest rate curve. Normally, when you buy a state bond, the longer the term, the higher the interests. Thus, a ten-year bond will yield a few cents more than a three-month bond. On the so-called secondary markets, where the bonds are exchanged, it is actually the contrary that is taking place. In an effort to secure their capital as the coming storm approaches, investors are turning massively to long-term bonds. As a result, their prices are going up and their yields are going down. So you see 10-year bonds earning less than three-month bonds. Experience has shown that such a phenomenon foreshadows negative growth in the course of the year : this is called economic recession.

The second phenomenon is more spectacular yet. These are the negative interest rates. After the serious 2008 crisis, Western economies have slowly recovered, mainly thanks to the decision taken by the central banks to bring the interest rates down to a near-zero rate. This measure was aimed at encouraging business to invest in the real economy in order to give it a boost. However, instead of jumping at the opportunity, business chose to buy its own shares on the stock exchange, which amounts to a non-productive investment. On the one hand, the wealthiest decided to invest in real estate, thus pushing up housing prices. On the other hand, the small savers lost on both scores: given the low interest rates, their savings no longer yield anything while housing sales and rental prices are soaring. In the meantime, speculators are licking their lips in anticipation.

Since they are foreseeing bad results on the stock market, investors have rushed into state bonds, increasing demand up to the point that more and more countries are issuing bonds with negative returns. In other words, one has to pay interest in order to lend money to the state. Twenty percent of the state bonds go hand in hand with negative rates. Consequently, one has to dig into one’s own pockets in order to invest. A total of 16 trillion euros worth of negative rate bonds are currently in circulation2, including the total amount of German and Swiss twenty to thirty-year state bonds. In Belgium and France, their interest rate is zero. The fact that investors are prioritising security over performance is further proof that they are expecting yet another crisis.

2019 is not 2008

Today, the outlook is grimmer than ever since the 2008 recession, but the situation is not comparable. Indeed, the situation is currently more intricate in view of the catastrophic level of indebtedness of states, together with the neoliberal taboo that surrounds any supplementary public expenditure. For instance, the European Union is still refusing to relax its restrictive rules in the matter of public debt.

Another difference: the current world no longer has an engine capable of getting it out of the rut. Ten years ago, we could still rely on the BRICS (emerging economic powers, i.e. Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa), especially China with its ambitious investment policy. The Chinese economy is now in full transition, a path deliberately chosen. The new standard is based on 6% growth rather than the previous double-digit growth. We could sum up the situation by saying that we have come to the point where all the engines are failing at the same time.

And although China is, indeed, faring better than others, its progress is nevertheless twice as slow now as it was ten years ago. The country has decided not to let exports and low-cost production condition its growth any longer. China wants to develop its domestic market, to increase the purchasing power of its population, as well as its own investments in strategic sectors. It also wants to move up “the value chain”, especially by manufacturing its own components in ten high-tech sectors. To this end, it has defined a comprehensive plan called “Made in China 2025”, that is supported by the authorities in all possible ways. This also means that China will not behave the way it did in 2008 when, in the face of the global crisis, it had decided to invest on a massive scale in infrastructure projects.

Nowadays, it is giving priority to high added value sectors and progressively replacing low-cost production with high-tech production. This is a strategic transition from extensive accumulation based on the use of fresh manpower recruited in rural areas to intensive accumulation based on increased productivity. In such a context, 6% growth in China will not be maintained without efforts, and certainly not in the event of a further escalation of the trade war with the USA. In August this year, exports and imports to and from the USA were down 16 and 22% as compared to one year ago. And world exports have been declining for the first time.

In spite of the 2.6 trillion euros injected by the European Central Bank to stimulate a recovery, the European Union has never really recovered from 2008. If it is true that the purchase of state bonds has given wings to investors and speculators, what has that money been used for? Not, at any rate, for allowing industries to invest, as they were supposed to do: there has been no evolution in the field of investments in the European Union in the past ten years, neither has there been any in that of capital stocks per worker. The flow of capital received by the banks has only been used to create new speculative bubbles. The recent decision made by Mario Draghi, president of the ECB, to reactivate his bond-purchase policy has been met with strong opposition within the institution itself. Seven of the 25 members of the ECB’s board of directors, including the heads of the French, German, Dutch and Austrian central banks, have rejected his proposal, deeming it useless.

For its part, the European Union is locking any new public investment in a tight budgetary straight jacket. As a result, states have gone into debt to save the banks, but growth is not sufficient to generate surpluses. Thus, the European economy continues to sink, led in its fall by Germany, though the latter had managed until now to make the most of the situation and keep the EU afloat. However, this pillar of the European economy is no longer spared and is diving even faster than its counterparts in the eurozone. Since the end of 2018, German industrial production has been receding month after month; in June, it registered a decrease of 5.2% compared to the same period the year before, and 7.5% compared to the end of the year 2017.

This evolution is directly linked to China embarking on a fundamental change of course. Indeed, at the onset of the 2008 crisis, Germany was exporting its production mainly inside Europe. When its exports to the southern European countries started dwindling, it turned to the booming Chinese market and massively exported machines, luxury cars, chemical and medical supplies to that country. However, building on its new strategy and technological development, China now depends less on imports from abroad. In addition, imports from Germany are being adversely affected by custom duties imposed by the USA.

Yet the collapse of Germany could lead to the collapse of its suppliers. And they are many. Germany represents no less than 29% of the eurozone’s GDP. One out of four of its workers is employed in the export sector. The Belgian, Dutch, as well as the French and Italian suppliers of spare parts will be directly hit by a default of Germany, and so will countries like the Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland, that have become, so to speak, subcontractors of the German industry.

This situation is compounded by the impending Brexit, the consequences of which at European Union level are subject to the most varied assumptions. Whatever the case may be, this event is bound to disrupt trade flows and, in many cases, bring about price increases due to the lack of new trade agreements. The European Union’s trajectory is increasingly reminiscent of that of Japan, which, from 1990 onwards, never managed to emerge from slow growth or stagnation in spite of countless monetary stimulus measures.

The only unknown factor remains the USA and its unpredictable president. Donald Trump’s accession to power was mainly due to the promises he made to revitalise the economy and to create jobs, including a substantial investment plan and a reduction in taxes on the wealthy and on corporations. In fact, only this last measure has been implemented and its results are still forthcoming. Thanks to its 4% growth rate, the Fed has been in a position to raise its interest rates for the first time since 2009. In the meantime, however, the US economy is also on a slippery slope, which has recently led the Fed to lower its interest rates. Trump would like to accelerate this process as much as possible as he intends to boost economic growth with a view to being re-elected in 2020. To achieve his goal, he is putting pressure on Jerome Powell, chair of the Fed. However, the latter believes that interest rate manipulation will not be enough to solve the problems posed by the trade war between the USA and China.

According to the latest figures, investment and production are at half-mast. The US president also insists on introducing various taxes on imports from China, as well as on imports of cars from Europe and Mexico. This would mean that as of the end of 2019, some 95% of all imported products would be subject to taxes ranging from 15% to 30%. With average import duties of more than 10%, the USA would go even further than already highly protectionist countries such as Brazil and Argentina. The consequences of such measures will inevitably affect the consumer goods sector and the household budget. It is estimated that their spending may rise by 500 to 1,000 dollar due to price increases.

The application of additional taxes of 15% on equipment, clothing, footwear and a whole series of electronic devices, scheduled for 15 December, will hit US households hard in the middle of year-end purchases, with a definite impact on the health of the consumer goods sector, responsible for 75% of the growth. As we can see, the United States is also likely to expect zero growth in the coming months.

Collapse or progressive slide?

If the contraction of economic activity at global level is now a reality, should we also expect a spectacular collapse like in 2008? A stock market crash is possible: everyone agrees on the fact that stock prices are clearly overvalued. Since 2009, the US stock exchange has been growing at an almost constant prodigious rate that does not at all reflect the growth figures of the US or global economy. With the arrival at the White House of stock exchange favourite Donald Trump, Wall Street is rejoicing, with a huge increase from 17.888 to 27.000 points. Speculators are trying to capitalize on this as long as possible in the hope that they will be able to remove their chestnuts from the fire in time before the collapse. If, however, they allow themselves to get caught by surprise on a large scale, we will face a crash that will sweep away all fictitious wealth, shake the financial world, and dragging in its fall the real economy as well. And an unexpected event could make this happen at any time.

But a gradual shift is also possible. Unlike in 2008, we are now seeing the trade war contract more and more economic activities, to the point of suffocation. So far, attempts to get out of the rut, whether by monetary means, by lowering interest rates or by acquisition measures taken by national banks, have yielded virtually no results. However, a period of acute crisis can cause real chaos and requires radical choices. It will inevitably be necessary to abandon the dogma of the law of the market and to opt for a plan of public investment capable of realizing a real social and ecological revolution.

Transition towards a sustainable economy will not be achieved without important investments, a prerequisite if we want to keep climate change within sustainable rates. The implementation of such measures must be accompanied by the productive use of surplus capital, which is currently being exchanged in a sterile manner within monopolies, investment and speculation funds and, finally, between the wealthiest 10% of the population. This money needs to be used to fund the public investment necessary for the green transition, as proposed by Bernie Sanders and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez in their New Green Deal.

Historically, it is known that the intensification of class struggle is the only way to make the bourgeoisie bend when it sees its interests threatened to the point of making the system falter, and this is exactly what the international leaders fear: they fear that an unsolvable economic and environmental crisis could lead to the need for a new model of society, namely socialism 2.0, which would put people’s needs, not profit, at the heart of its policies.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The root causes of the crisis

We often hear that capitalism does not exist without growth. So how is it possible that growth has been stagnating at a virtually zero level for more than ten years in the Western world? Instead of giving serious answers to this mystery, the media are still looking for external causes: one day the banks are to blame, another day the stock exchange, yet another day the level of confidence or the trade war. However, we will never hear that capitalism itself is to be blamed.

And yet, it is true that there is no capitalism without growth. According to Marx’s analysis, the engine of this growth is the cycle of accumulation. Capital is invested in order to yield returns, to generate profit. Capital has to be accumulated, it has to grow, and to achieve this it needs workers who will ensure production at the lowest possible cost. All the wealth produced therefore comes from labour, that is also the only source of profit. The more profits a company makes, the more it can invest to eliminate its competitors. The market fanatics see this as a fantastic mechanism that guarantees prosperity and allows us to increase wealth again and again. According to them, the public authorities should intervene as little as possible, since the profit hunt carried out by the owners of the capital is sufficient to oil the workings of this system.

However, the reality is altogether different. Capitalism shows its limits and its failures with clockwork regularity. Historically, it is more marked by periods of crisis than of prosperity. The root cause of this failure lies in its internal contradictions.

According to Marx, the explanation of this phenomenon is to be found in various factors. First of all, while human labour is the source of wealth, capitalists are constantly looking for ways to save on labour costs. This inevitably leads to the depletion of wealth and, in the long term, a downward trend in the profit rate. Capitalists do not invest anymore because of insufficient profit expectations. Secondly, the relationship between production capacity and purchasing power tends to become unbalanced: in order to produce more and at low cost, wages are forced down… which limits the purchasing power of workers. Furthermore, capital flows to the most profitable sectors, which can lead to overproduction. Finally, employment, salaries and social security are subjected to austerity measures that paralyse or at least restrict purchasing power, making the situation still more complicated.

When these factors coincide and reinforce one another, all the conditions are met to provoke a long-term crisis that will not be resolved with measures such as lower interest rates or monetary stimulus. This is precisely the situation we are observing today.

---------------------------------------

1. The ECB has been buying bonds in bulk for amounts of up to 80 billion euros per month since 2015. The sum total of the bonds currently at its disposal amounts to more than 2.6 trillion euros.

2. The PMI measures the evolution of industrial growth in 40 countries each month. When it is stable, the index shows 50. A value greater than 50% indicates an expansion of industrial activities, whereas a value less than 50% indicates a contraction of these activities. It is a “weighted” index, which means that the effect of countries on its changes is proportional to their size.

3. Jannick Damgaard, Thomas Elkjaer, and Niels Johannesen, “The Rise of Phantom Investments”, IMF, Finance & Development, September 2019.

4. De Tijd, 24 August 2019, “Waarom zou helikoptergeld niet mogen en absurde negatieve rentes wel?”